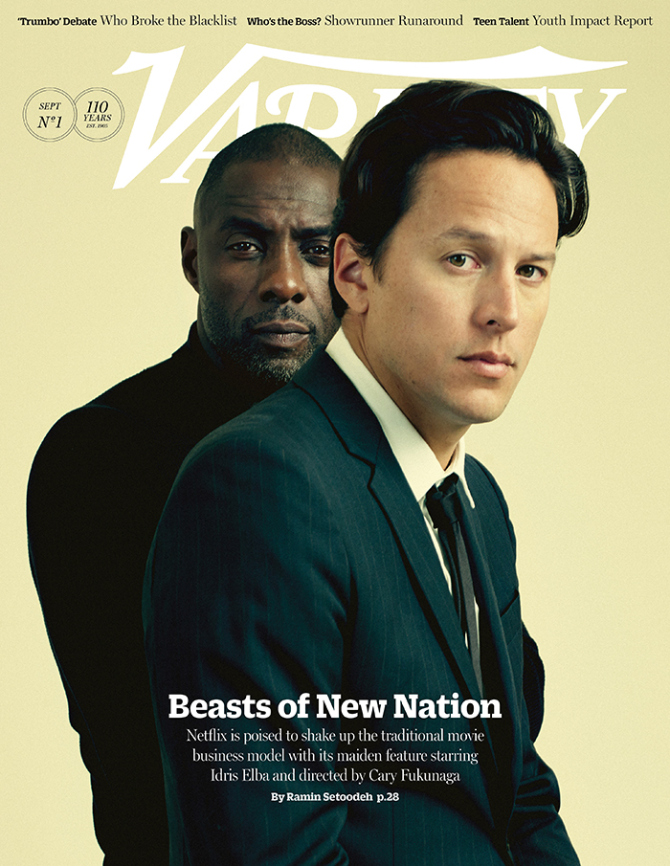

Ramin Setoodeh | Variety

Idris Elba nearly plunged to his death filming Cary Fukunaga’s “Beasts of No Nation.” The indie drama, about an African tyrant known as “the commandant” who recruits an innocent boy into his army of youth soldiers, took Elba into the depths of Ghana’s jungles for a guerrilla-like shoot. One afternoon, as the actor waited for the next scene, he leaned against a tree overlooking a waterfall, lost his footing and fell over the ledge. Luckily, there was a narrow ridge that saved him from a 90-foot drop.

“I remember slipping and catching onto this big branch that was sticking up, and I literally was like, ‘Whoa!’ ” recalls Elba. “It was a moment where I was like, ‘This is the real deal.’ ”

“Beasts of No Nation” wasn’t just a high-stakes, death-defying production for its cast and crew. It’s also a dive off the cliff for Netflix, which acquired the movie for a whopping $12 million last winter, as part of a plan to upend the conventions of the film business in the same way it has transformed traditional TV viewing with original series such as “Orange Is the New Black,” “House of Cards” and “Daredevil.”

This week, “Beasts” enters the triple-gauntlet of film festivals (starting with Venice and Telluride, followed by Toronto), premiering Oct. 16 on Netflix, the same day the film opens in platform release on 29 screens via distributor Bleecker Street. Netflix already has committed to backing its inaugural feature with a formidable awards season push, and a massive ad campaign of billboards, TV spots and online trailers. But because the major chains — AMC Theatres, Regal Cinemas, Cinemark Theatres and Carmike Cinemas — still refuse to show titles that aren’t exclusive to multiplexes, the only venues that “Beasts” can occupy are arthouse screens like the Alamo Drafthouse chain. “Netflix will have to prove its value to theater owners,” says John Fithian, president of the National Assn. of Theatre Owners, who admits to streaming movies at home.

This week, “Beasts” enters the triple-gauntlet of film festivals (starting with Venice and Telluride, followed by Toronto), premiering Oct. 16 on Netflix, the same day the film opens in platform release on 29 screens via distributor Bleecker Street. Netflix already has committed to backing its inaugural feature with a formidable awards season push, and a massive ad campaign of billboards, TV spots and online trailers. But because the major chains — AMC Theatres, Regal Cinemas, Cinemark Theatres and Carmike Cinemas — still refuse to show titles that aren’t exclusive to multiplexes, the only venues that “Beasts” can occupy are arthouse screens like the Alamo Drafthouse chain. “Netflix will have to prove its value to theater owners,” says John Fithian, president of the National Assn. of Theatre Owners, who admits to streaming movies at home.

Despite some resistance, Netflix’s entrance into the movie business will be a game changer. Unlike theatrical distributors, whether Disney or Fox Searchlight, the video-streaming goliath doesn’t need to rely on ticket sales to measure a film’s success. Rather, Netflix makes money through its paid subscriber base, which is 65 million and growing. The Los Gatos, Calif.-based company is moving its Southern California headquarters from Beverly Hills to Hollywood by 2017, doubling its L.A. office space, with plans to occupy 200,000 square feet in the 14-story Icon Building at Sunset Bronson Studios.

“There’s no theatrical revenue expectation in our business model on any movie,” says Netflix’s chief content officer Ted Sarandos, who has been on a features buying spree (he’s expected to spend more than $500 million on original content next year). In the months to come, Netflix subscribers won’t have to leave their sofas to watch Adam Sandler’s new Western “The Ridiculous Six” (debuting Dec. 11); martial arts sequel “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon: The Green Legend” (early 2016); “Pee-wee’s Big Holiday,” starring Paul Reubens (March 2016); “Jadotville,” a true-life drama headlined by Jamie Dornan; and the Brad Pitt military parody “The War Machine.”

“I feel like it’s incumbent on us to make and distribute movies that are so good that theater owners will want to book them,” says Sarandos, arguing that limited access to first-run movies is bad for business. “Every single bit of media in the world has been impacted by the Internet — books, television, music; everything, except for the window of theatrical movies,” he notes.

Sarandos says that Pitt never asked about a theatrical release (“they aren’t thinking about the size of the screen”), and Sandler decided not to put “Ridiculous Six” in theaters after the major circuits wouldn’t carry the film. “Adam believes his audience is mostly at home, and he’s probably right,” Sarandos explains. “It’s not like Adam is no longer making theatrical movies. He just wanted this movie to go day-and-date with Netflix, and the theater owners didn’t respond to booking it. I think they’ll regret it.”

Exhibitors have long fought to preserve a 90-day window as the period between a movie’s theatrical release and availability in homes. But as a sign of the times, Paramount has convinced some chains to agree to a substantially shortened window for two of its fall releases, “Paranormal Activity: The Ghost Dimension” and “Scout’s Guide to the Zombie Apocalypse,” in exchange for a cut of the VOD revenue. “My opinion is that window models need to be more sophisticated,” Fithian says. “We know not all movies are the same.” Hollywood is watching closely to see if Netflix’s ballyhooed arrival in the movie world will further collapse windows, especially for small titles that have been struggling at the box office — like this summer’s Sundance darlings (see “Me and Earl and the Dying Girl” or “Dope”). “It has to change,” says Amy Kaufman, a producer on “Beasts.” “There have to be more distribution opportunities for us to be able to keep making these films.”

Sarandos pledges that Netflix’s slate will be much more diverse than those of studios. “We’re trying to make the films that are not getting made,” he says. He also doesn’t count out also financing a $150 million tentpole like “Jurassic World” — the last movie he saw in a theater. “We are producing on that scale on our TV series,” he says. “It wouldn’t be that big a leap.”

On paper, “Beasts” is an undeniably non-commerical tale about the tortured world of child soldiers, set in an indeterminate country in West Africa. Its cast consists of unknowns, headlined by breakout newcomer Abraham Attah (who plays the lead, Agu). Where a traditional studio might devise an advertising campaign that masks the film’s violence, Netflix isn’t holding back. The film’s first trailer depicts a brutal scene where Agu hacks a man’s skull with a machete. “There were many questions asked early on from financiers about how I was going to execute the violence,” Fukunaga says, adding that bloodshed is a theme that runs through most of his stories. “The brutality I show in the movie is not even a 10th of the violence you see in a war. Yet it’s really hard for people to stomach.”

Netflix’s acquisition of “Beasts” illustrates the kind of roller-coaster ride the indie film business has become. Fukunaga started to prepare the drama after his run as the director on the first season of HBO’s “True Detective” last year, but he’d been laboring on the adaptation of Nigerian author Uzodinma Iweala’s 2005 novel for nearly a decade. While making his first movie, 2009’s “Sin Nombre,” for Focus Features, Fukunaga set up “Beasts” there with then-CEO James Schamus. But shortly thereafter at Sundance, the French-made “Johnny Mad Dog,” about child soldiers in Liberia, failed to secure a U.S. distributor, and Focus put Fukunaga’s dream project into turnaround.

Around 2010, the story’s rights reverted to the author, and Fukunaga and producer Kaufman bought it themselves. Manhattan-based Red Crown Prods. — led by partners Daniel Crown and Daniela Taplin Lundberg — were able to scrounge more than $5 million to produce the story, with the help of Participant Media. “I remember reading it, feeling like the screenplay had such heart, I wept,” Taplin Lundberg says. Participant was drawn to the film’s social message, given that there are an estimated 300,000 children trapped as soldiers around the world. “It’s a real problem that makes sense for us as a movie,” says Participant executive vice president of production Jonathan King.

Fukunaga prepped for the 35-day shoot in late 2013, and reveals he always intended to leave “True Detective” after the first story arc. The director admits he hasn’t watched the panned second season, but he’s aware that writer-creator Nic Pizzolatto added a diva-director character seemingly aimed at mocking him. “I have friends on the crew who told me about it. What’s there to make of it?” Fukunaga says with a laugh, declining to elaborate further. He hasn’t communicated with Pizzolatto since he saw him at the Golden Globes in January. Responding to Variety, Pizzolatto says: “The director character in episode 3 was absolutely not meant to represent or allude to Cary in any way. The actor (Philip Moon) was hired because I was a fan of his from ‘Deadwood,’ and he arrived with the look he had.”

Fukunaga is much less guarded talking about “Beasts.” He cast Elba first, knowing the star of “The Wire” had the natural charisma to add layers to the despicable commander. The actor was drawn to the material, given that his mother was from Ghana, a country he’d never visited. “Here was this really beautiful point of view which was fascinating for me,” Elba says. “We could make a war movie, but this was about a boy coming of age within a new family. How do you humanize someone that’s a dictator to any army of kids? That was massive challenge to me.”

As Fukunaga scouted locations in Liberia and Sierra Leone, he knew he had to shoot in West Africa to be authentic to his story. Insurance eventually cleared the production for Ghana, where a U.S. movie had never shot. Fukunaga’s casting director, Harrison Nesbit, arrived on the ground shortly before the production was set to begin to find the unknown locals who could carry the picture. Attah, who had never acted before, impressed Fukunaga by crying on command during an audition exercise. “He’s 14 — maybe 15,” Fukunaga says. “It’s hard to say. He would change his age depending on what he thought we wanted him to be.”

Fukunaga’s stories from the shoot sound like a cross between Jacques Cousteau and Huckleberry Finn. He says that on the Saturday before he was scheduled to start, he felt worn down. By Sunday, he was so exhausted he stayed in bed, and a doctor diagnosed him with stage-two malaria. “It’s like someone gave you a sleeping pill, along with a pounding headache and a hot-and-cold fever,” Fukunaga says. “My entire body ached. My kidneys were aching.” The production had to push back a week as the director recovered.

But getting malaria was only the first in a series of disasters for “Beasts.” The camera operator pulled his hamstring on the first day, which meant Fukunaga had to fill in on that job, in addition to his roles as director and cinematographer, using a Steadicam strapped to his back. Some of the extras playing the tribal guards were jailed in the Ivory Coast on suspicion of being mercenaries, and had to be sent money for food and clothes. Actors wouldn’t show up for work because they lost interest, forcing Fukunaga to crank out morning rewrites. The cast was terrified of poisonous snakes, and the director — who travelled through the jungle with a machete and a stick — nearly stepped on a black mamba that could have killed him.

The film ballooned $1 million over budget, and Fukunaga found himself struggling to keep it together. “Every day, it felt like we were on a sinking ship,” he says. “I thought, this is going to be ‘Lost in La Mancha.’ We were shooting in rainy season. Sets were washing away.” Fukunaga shed 20 pounds from his 180-pound frame. Because he didn’t trust the local meat — “In Africa, you see chickens and pigs eating garbage,” he says — his diet frequently consisted of a salad of onions, cucumbers and avocado. “I just found out last week I’d been carrying a parasite for the last year, so that was probably part of the weight loss,” Fukunaga says. “I’m on a whole cocktail of antibiotics now.”

The director returned home in July 2014 more exhausted than ever. “For months, I had dreams we were trying to shoot, and things weren’t happening,” he recalls. “People would have conversations with me, and I would sound drunk in the dream, because I couldn’t put my words together, I was so tired.” As he started to slowly cobble together an edit, he was fully aware that he had never finished shooting all the scenes he needed, and would have to close some gaps with voiceover. Meanwhile, his investors were concerned they’d never get a dime back.

Because Focus had originally bought “Beasts,” it had first right of refusal on the finished film. The studio saw a cut in December 2014; Netflix then saw the same cut a month later, and that’s when it put down its hefty bid. Riva Marker, Red Crown’s production president, said the company was “blown away” by the offer. “It’s an independent producer’s dream that you make a movie and sell it for double its strike price,” she says. When Focus passed on the film, Netflix laid claim to its first major acquisition. Explains Sarandos, who has seen the movie six times now: “It struck me, as we’re getting into the film business, we should be picking projects that are exceptional films, and otherwise difficult to distribute.”

Netflix’s $12 million offer for “Beasts” was meant as a single lump payment, since there would be no back end tied to box office or DVD sales. But it was generous enough to allow all the investors, and Elba (who served as a producer), to turn a tidy profit. “I’m very happy that Netflix bought it,” the actor says. “The silver screen will always be the silver screen. But now a small film like this, with a very tiny budget, is going to get viewers.”

Fukunaga was initially more cautious. He wanted audiences to see “Beasts” on the bigscreen, which is why Netflix added a theatrical component. “I was nervous it would just be an online film,” Fukunaga says. Yet he realizes that most viewers will see “Beasts” on their TVs. “I just hope they watch it all the way through,” he says. “When you watch at home, you’re tempted to watch in pieces, and the emotional experience is interrupted.”

Netflix will put all its marketing might behind “Beasts,” giving the movie a big Oscars push, with the help of awards season consultant Cynthia Swartz from Strategy PR. The movie will compete in the major categories, and the blogosphere is already buzzing about Elba being a contender in the best supporting actor race. Sarandos notes that Netflix had success with campaigns for its documentaries “The Square” and “Virunga,” which were both nominated, although he’s not sure how Oscar voters will respond to a Netflix narrative drama.

But in line with “Beasts’” unconventional release strategy, Fukunaga is also the rare awards season contender who doesn’t sound like a seasoned politician. “I think it’s a long shot,” he allows. “It’s not an Oscars kind of movie. It’s not a feel-good film. I don’t know if older audiences are going to respond to it. But I also didn’t know if people were going to like ‘True Detective.’ ”