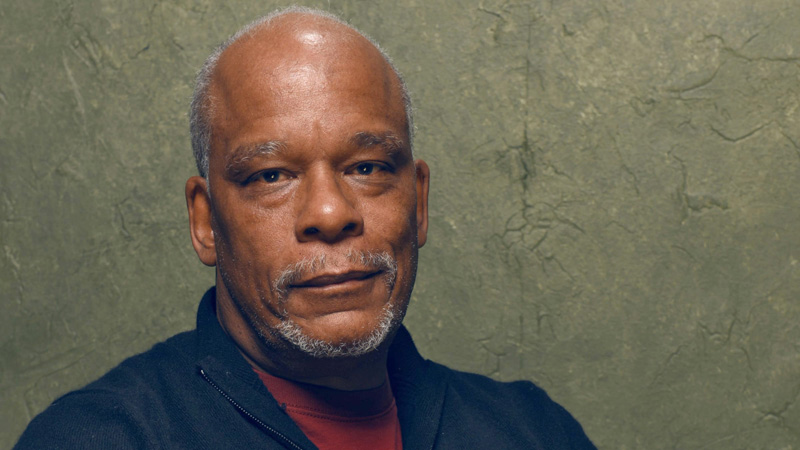

Larry Busacca/Getty

By Cynthia Littleton | Variety

In the 1980s, it took Stanley Nelson seven years to make “Two Dollars and a Dream: The Story of Madame C.J. Walker,” his first documentary film. It took him another seven years to make his second feature doc: “The Black Press: Soldiers Without Swords.”

Once he had two films under his belt, Nelson, now 66, was on his way to becoming one of the foremost and most prolific documentary filmmakers to chronicle the Black experience in America. Nelson’s notable recent films include “Miles Davis: Birth of the Cool,” “Tulsa Burning: The 1921 Race Massacre,” “The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution” and the upcoming “Attica.”

As he forged his path, Nelson realized the desperate need for training, mentorship and other programs to open doors for filmmakers of color to allow them to have meaningful careers in media. At a time when Nelson’s Firelight Films is busier than ever with movies and docu series productions, the non-profit Firelight Media arm is in its 12th year of running the Docufilm laboratory course for promising documentarians.

In recognition of his body of work and his commitment to trying to give others what he calls “a leg up,” Nelson was selected by Variety and Rolling Stone as the inaugural recipient of the Truth Seekers award honoring extraordinary contributions to documentary filmmaking. The award was presented Aug. 26 as part of the daylong Truth Seekers conference, hosted by Variety and Rolling Stone, to examine the explosive growth in documentary and nonfiction production.

In accepting the kudo, Nelson took part in a wide-ranging virtual conversation about his career with Variety contributing writer Addie Morfoot.

Nelson noted that the expansion of the documentary form and the number of outlets pursuing high-end nonfiction production has been transformative. A few years ago, he sat down with his partners at New York-based Firelight Films to decide whether the company should step up its volume of production as so many offers to produce features and multi-episode series began to flow in. Until a few years ago, Firelight primarily made one major film at a time. Not any more.

“We said, let’s go for it,” Nelson said. “Let’s see how much more we can do and how many more people we can work with as employees, because that’s our mission in the same way that it’s the mission of the Documentary Lab — how can we get more people of color into the industry? How can we employ more people who can then go on and fly on their own.”’

Nelson is low-key and completely matter of fact as he explains the extra burden that Black filmmakers, executives, talent representatives and creatives shoulder when they gain a measure of success. He created Firelight’s Documentary Lab, with the support of foundation grants and institution charitable sources, in order to streamline the unofficial guidance that Nelson and his small group of industry peers were already dispensing on a regular basis.

“We wanted to think about was, how do we give people a leg up? How do we give people a start? Not only myself but so many filmmakers were serving as mentors — informal mentors to other filmmakers and especially filmmakers of color. People would call me up, literally out of the blue, just saying, ‘I saw a film that you made and, uh, you know, you’re a Black filmmaker, I’m a Black guy, could you be my mentor?’ And it was not only me, it was other filmmakers, too. And so we wanted to try to think about institutionalizing this and making it something that was more of a program instead of just ad-hoc or catch as catch-can. And that became the idea for the lab.”

Nelson and Morfoot spoke of the documentary boom and the streaming revolution that has leveled the distribution playing field for docs. But the spike in orders has gone largely to established producers who have worked with major networks in the past. That makes it hard for new voices to break in even when streamers with deep pockets seemingly can’t order docu series fast enough.

“People are looking for new and inventive docs about different subjects. And so it’s really allowed people to expand the form. It’s a golden age for docs for some people,” he said. “So if you’re kind of high up on the food chain – which for whatever reason, probably because I’m just old and been doing it a long time, I am — it’s a golden age. You know, people are actually calling me on the phone and wanting to help me make things. But we work with a lot of first-time filmmakers. And for them, it’s still a struggle getting their first film made. And it’s still a struggle many times getting their second and third films made. So I think it’s a golden age for some people, but a lot of doc filmmakers are still struggling to get projects made.”

Among other highlights from the conversation:

On research: Nelson said there’s not much mystery to the research process on his documentaries. Nor does he have a large staff in that area. “We just read the books and talk to people and follow the story and let it go where it goes.”

On the “illusion of objectivity” for docu filmmakers: Nelson is an old-school filmmaker who does not take advocacy positions in his films. He tries to present a warts-and-all portrait of the people and institutions on which he has trained his lens. Documentary films “try to have the illusion of objectivity. I don’t think that there’s complete objectivity but we at least want appear that we’re objective and that we’ve done really deep research into the subject,” he said.

On “Attica” premiering at the Toronto Film Festival and Showtime: Nelson is eager to see his film about the notorious 1971 prison uprising in New York with a live audience. The film features interviews with men who were young inmates at the time who have never spoken of their experience. “I’ve never been to the Toronto Film Festival before — I’m really excited about going,” he said. “I think that that ‘Attica’ is a really shocking and important film. And so I’m just dying to see a film with an audience.”

On advice for aspiring documentarians: “You’ve got to like making docs, you know? You’ve gotta like watching docs, you’ve got to like the form. If you do, then you have a chance for longevity because you like what you do,” Nelson said. “You know, one of the best things that ever was said to me is when I was working as an assistant producer by an older filmmaker. He said to me, ‘You’ve got to enjoy the journey.’ You’ve got to enjoy the process. You’ve got to enjoy the people that you meet in the situations that you get in. You have to enjoy those things because you might not remember if you put in this shot or that shot — so it’s really important that you enjoy the journey.”