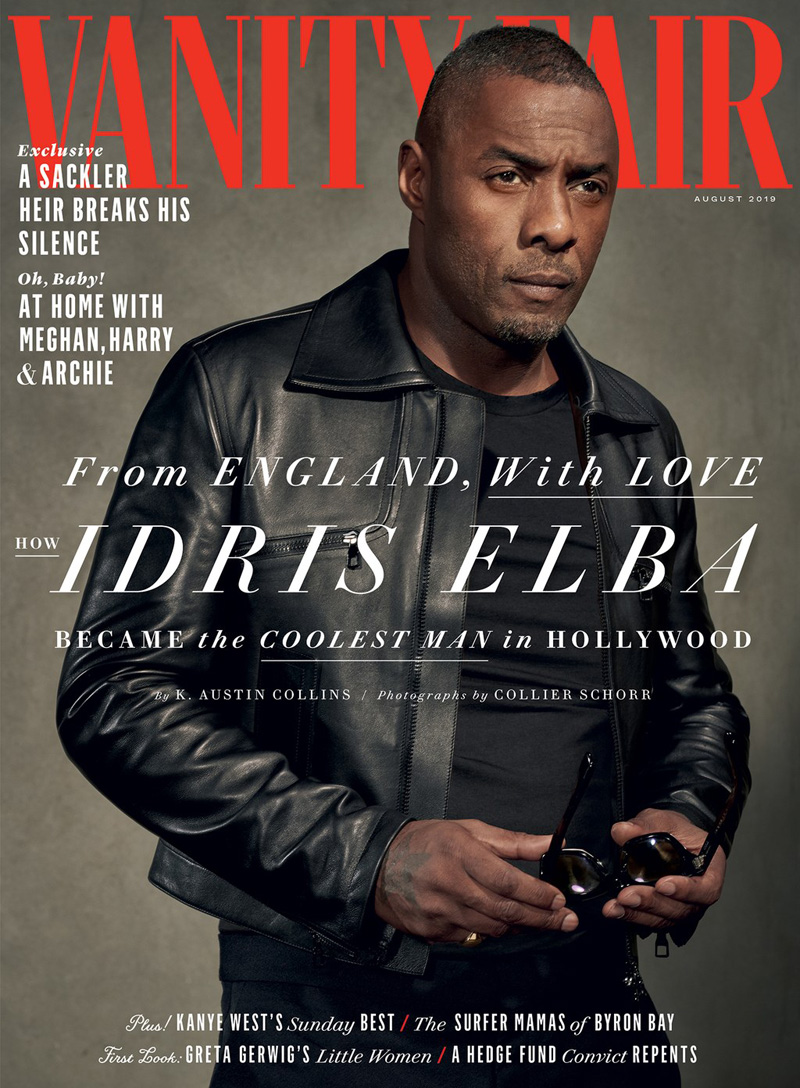

From prestige TV to tentpole franchises to the Coachella DJ tent, the British actor is a poster boy for 21st-century fame: multidisciplinary, omnipresent, engaging. So what does Idris Elba want to do next? And what do we want from him?

He’s smooth—obviously. And tall. An hour into meeting him, I can’t help but continue to notice as much. We are deep into a conversation about growing up black and British in the ‘80s and wanting to be a movie star: what that must have felt like to young Idrissa Akuna Elba, the first-generation working-class son of Ghanaian and Sierra Leonean immigrants, who’d grown up in Hackney and East London’s Canning Town, areas where the far-right National Front party had strongholds. It’s a complicated history. “Needless to say,” he tells me, “if you were black and living in Canning Town, you were probably subject to racial abuse and getting chased down the street by people calling you a black coon.”

But he doesn’t dwell, preferring to tell a different story. At 13 he met a drama teacher, a Welsh woman named Miss McPhee, who sparked something in him. “I remember just being fascinated,” he says. “She’d be like, ‘So’ ”—he slips into a lively, declarative teacher voice—“ ‘I want you guys to pre-tend to be a frying egg. An egg in a frying pan. What would that feel like?’ ” He imitates his fellow classmates, all of them rowdy teenage boys, refusing to participate. And then he gives me a rendition of his performance: a fury of convulsions, his mouth serving up popping and sizzling sounds—splattering grease by way of Daffy Duck.

“ ‘You’re really good at that,’ ” he says, again channeling Miss McPhee. “ ‘Have you ever fried yourself?’ ”

Idris Elba, now 46, attractively grizzled and low-key in a T-shirt and trackies, is more fit than fried. He’s wearing a shirt with the message “Don’t Stab Your Future,” a nod to the problem of knife crime—violent street offenses involving knives—in England and Wales, which have seen a rapid increase in incidents in recent years, disproportionately affecting young men of color. After our interview, he’s headed to appear on BBC’s The One Show to talk about the issue—a privilege, he says, because “having a massive soapbox is useful.”

“There were a handful of black actors and performers in this country, in the music space,” he says, looking toward the window with each exhale. “Reggae, which was a shared, big U.K. experience. English people love reggae. Because the majority of black people in this country were from the Caribbean, they came with the music. So you were seeing, on TV, reggae bands, reggae-white fusion bands. But in terms of actors, there were very few.”

There were standouts—the comedian Lenny Henry, of The Lenny Henry Show, for example. But mostly Elba grew up watching the black stars that black people worldwide, to say nothing of everyone else, were watching: Sidney Poitier, Harry Belafonte, Richard Roundtree. And later: early-career Wesley Snipes and, of course, Denzel Washington, who in the late ‘80s came to England to film For Queen and Country, the story of a black paratrooper who joins the British army to escape poverty, fights in Northern Ireland and the Falklands War, and struggles to integrate when he returns home. Elba remembers reading, later, that Washington was getting an education about black Britain during filming—one clarified for Elba when, after moving to the States, he’d meet people who’d say, “You’re English? There’s black people there?”

“When I got to America and was like, I want to be an actor, I was like a novelty act in all my casting meetings,” Elba says. It was something the Americans hadn’t encountered before and didn’t know, yet, how to use. Now there are enough black Brits in Hollywood that an American actor like Samuel L. Jackson could, fairly or not, complain about what it means for his black American counterparts, as he did in 2017, and as characters on the newest season of Spike Lee’s She’s Gotta Have It debated, to some controversy, just this spring.

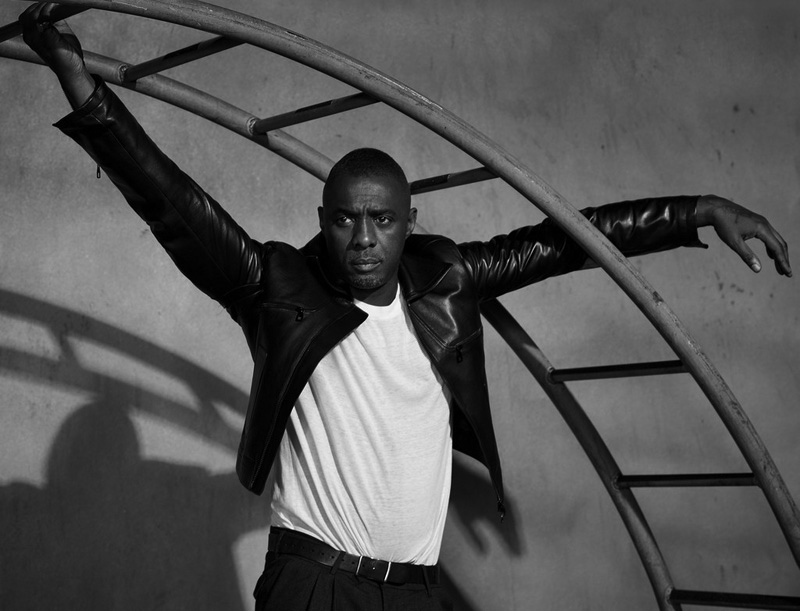

Photograph by Collier Schorr; Styled by Ludivine Poiblanc.

But that wasn’t the climate in those casting sessions, when Elba was starting out. “They were like ‘Wow! I love your accent, it’s so refined,’ ” he says, eyes widened in imitation. And then: “ ‘Okay, so: you’re Gangster No. 1.’ ”

He has a sense of humor about it now.

We’d agreed to meet in the cozy Camden Town offices of Elba’s production company, Green Door Pictures. Founded in 2013, the company has yet to produce a film in which he or anyone of his caliber plays Gangster No. 1. It likely never will. Those days are long behind him. His packed résumé is proof enough. He’s had three television series air over the past year alone, including the fifth season of his Emmy-nominated crime drama Luther. His recent movie slate includes the release of Yardie, his directorial debut; an upcoming film adaptation of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Cats; and, this month, Fast & Furious Presents: Hobbs & Shaw. Further proof of Elba’s ascendance: his office, which sits nondescript behind what looks like a posh, overlarge garage door fitted with white-tinted windows. It’s a workday. Downstairs, his staff is busy being busy. Upstairs, tucked away in a recording studio with a pair of producers, a promising young woman named Anna is laying down a track.

Elba, an established DJ and recording artist, sees music as central to the mission of his production company. Same for his family. His five-year-old son, Winston—named for Elba’s father—is playing with his toys a room over from us, so quietly that I almost forget he’s there. Elba has a teenage daughter too, from his first marriage, though they don’t live together. Meanwhile, there is news on the horizon. Not long after we meet, Elba announces that he’s gotten married again, in a sunny Marrakech ceremony, to the model Sabrina Dhowre.

So—it’s been a banner year and, frequently, a surprising one. There’s been a little more comedy than usual, what with the goofy self-effacement of his Netflix show, Turn Up Charlie, about a DJ bachelor who becomes a nanny, and a recent gig hosting Saturday Night Live for the first time. There’ve been the music successes too. This April he performed a slick two-hour set offering his usual mix of house and hip-hop at Coachella that Vulture, hardly able to contain its surprise, called “actually great”—an accomplishment only bested, in once-in-a-lifetime implausibility, by his gig DJ’ing at Meghan Markle and Prince Harry’s royal wedding last May. The prince personally asked him to take the job.

This is a far cry from the relative unknown who, in the early aughts, took the American television scene by storm with his depiction of Stringer Bell on HBO’s The Wire. And Bell himself is a far cry from the man perched in front of me. Elba has a knack for lending his roles, even minor ones, an attractive veneer of mystery which, in person, he lacks. Five feet from you, he’s an amicable, open, energetic, talkative man. That must be why they call it acting. Or maybe it’s just the Stringer Bell effect: Whoever he is, you can’t watch him without wondering where he’s been and how he came to be, even when he is the bad guy. His is a movie-star magnetism: Part of his appeal, you realize, is how utterly convinced you are that what he’s giving you is honest. You believe it, whether you like it or not. And a fast-changing Hollywood seems to be liking it more and more.

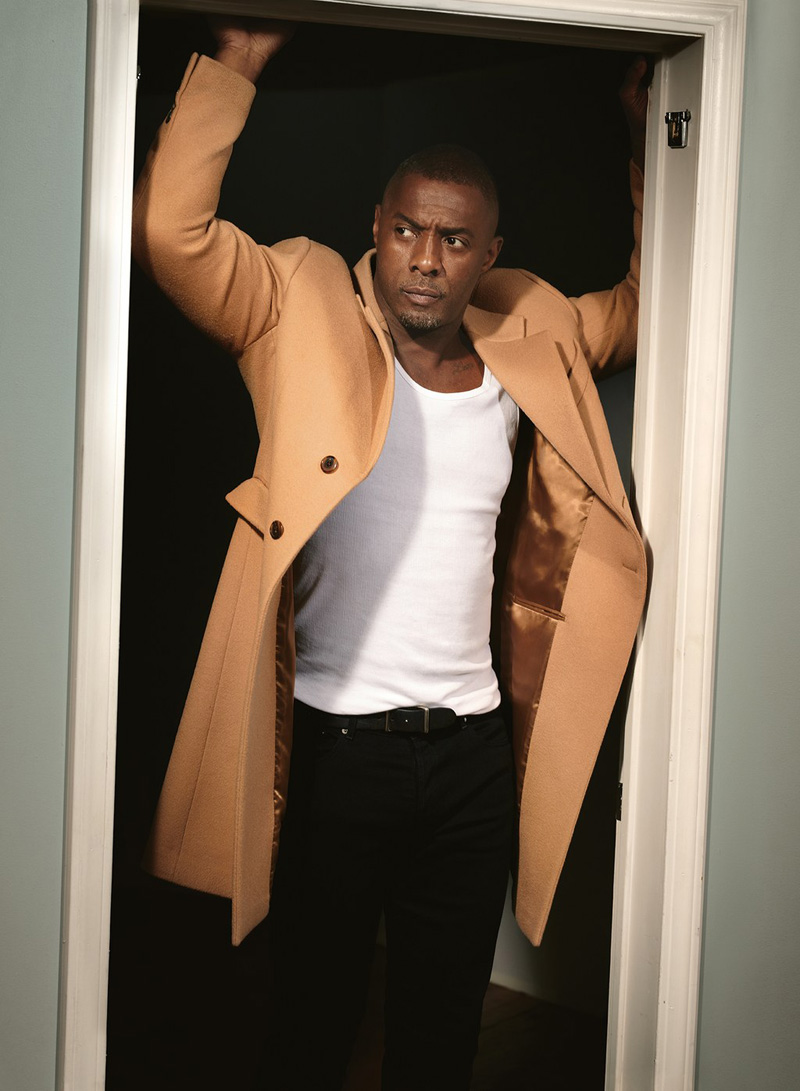

Photograph by Collier Schorr; Styled by Ludivine Poiblanc.

Elba was born in 1972, on the heels of multiple African and Caribbean exoduses to England. He was part of a generation of British-born blacks whose identities seemed multiply bound to each part of those migrations—not to mention, in Elba’s case, of his working-class upbringing. His new Sky-network show, In the Long Run, which is “kind of like Everybody Hates Chris, based on my life in the ‘80s”—is about the early chapters of his life in Hackney and Canning Town. He plays his father on the show, a man he describes as a “smooth cat,” his biggest male influence in life. The project helped him understand his father a little better. “Every now and again,” he says, “I get these moments of real emotional tension, because I’m playing my life back in the ‘80s, and there are moments where I’m like, Wow, I remember this story line, and this. I see it reenacted, and I’m playing him, and I’m thinking, Oh, shit, my dad was going through that. It’s a weird art-imitating-life, life-imitating-art sort of thing.”

His father worked for nearly 25 years at the Ford Dagenham auto plant, eventually becoming a shop steward after years on the factory floor. Soon after leaving school, Elba joined him—not exactly willingly. “I was 19, doing the night shift,” he says. “It’s not for anyone. So it just made me think, Man, when I get into acting and make it full time, I’m going to work hard, because if I can do this job, all night, mundane, boring, repetitive, then I’m going to be able to act.”

Elba’s transition to screen-acting is by now well-known. He arrived in New York long before he was legally eligible to work in the States, hustling to get auditions. He came over on his summer holidays. The routine of going to casting calls was drudgery—for any actor, but particularly for a black actor, and most especially for one with the size and stature of a ready-made gangster or basketball player. Gigs came. One, a pilot for Fox filmed in Canada, gave him a visa that allowed him to hop to the States for auditions when the time came. He moved to New York in 1997 and kept working: bouncing, selling weed. He landed The Wire in 2001.

You wouldn’t know from the mythos of Stringer Bell that he didn’t live past the third of the show’s five seasons—so essential was he to the fabric of its ideas about black life and black enterprise. David Simon, the series’ creator, told me that at the time of his departure, Elba wasn’t certain that his career was secure. Simon was. “I remember saying to him, ‘Once this airs, once they see the end of your arc, if not already, you’re going to have more work than you need. You’re gonna be doing films as a leading man,’” says Simon. “And he rolled his eyes and said, ‘From your lips to God’s ears.’” The prediction bore out: Elba’s career was pulled in multiple promising directions immediately afterward, some of which draw more attention than others. There was the return home, to England, to star in Luther. There’s the long run of franchise roles, many of them supporting, that have formed the backbone of his mainstream Hollywood career. Less discussed but just as important are the several roles Elba took in black American movies immediately after The Wire: films like The Gospel, This Christmas, Daddy’s Little Girls, and Obsessed, in which he played a maybe-cheating husband to one Beyoncé Knowles.

These weren’t prestigious movies; someone glancing at his IMDB page is likely to overlook them in favor of his bigger, “better” work. But for Elba, they were essential. “Yes, The Wire was a big show,” he says. “But it wasn’t the biggest show—at all. And the reason HBO extended the story line to three seasons instead of one is because of the upsurge in African American subscribers.” When he left the show, black producers and directors—“Will Packer, Tyler Perry, and the crew,” as Elba puts it—offered him a slate of roles that would make him a recognizable movie star for the black public, specifically. “The beginning of my world outside The Wire started there,” says Elba, who has for the most part left those films behind. “Now we’ve grown into this much, much bigger highway, and not only African Americans are watching African American films. There’s a wider spectrum of audience.”

He’s had his eye on bigger fish lately. His ambition seems to be to push the suave but down-to-earth intelligence he’s honed in his career to date into the mainstream, an aim that recently seemed to hit an as-yet-invisible limit, one that surprises anyone who’s grown to associate Elba with heroic complexity, protagonists whose moral heroism constantly wavers. I’m talking, of course, about Bond, James Bond. Rumors of his serving as the next 007 have taken on a strange and outsize place in Elba’s professional narrative these last few years. And with good reason: It would be an ideal role for Elba, you’d think. Speculation that Elba would be hired as the first black James Bond was sparked in part by a 2018 survey in the Hollywood Reporter claiming that 63 percent of Americans wanted him for the role, a reflection of, if nothing else, the changing times. It always seemed to have been more a matter of the will of the people than of actual prospects. He was, by all accounts, never seriously considered.

Elba confirms for me that this is not happening and adds that he doesn’t love to talk about it. “James Bond is a hugely coveted, iconic, beloved character, that takes audiences on this massive escapism journey,” he says. “Of course, if someone said to me ‘Do you want to play James Bond?,’ I’d be like, Yeah! That’s fascinating to me. But it’s not something I’ve expressed, like, Yeah, I wanna be the black James Bond.” He now has fun with the rumormongering, riling up fans with 007-esque tweets and a selfie with Daniel Craig.

It’s almost disappointing. The idea of a black 007 is intriguing, even opportune for a narrative shakedown or two. Picture it: a Bond whose advantages include not being the white guy everyone thinks they’re hunting for, but someone black, or a woman—or both. Blaxploitation movies used to make fun of scenarios like this, as have countless undercover-cop movies. “Because, by the way,” Elba says, “we’re talking about a spy. If you really want to break it down, the more less-obvious it is, the better.”

Which hasn’t made him any more eager to have the conversation. Here, his nonchalance wavers a little. “You just get disheartened,” he says, “when you get people from a generational point of view going, ‘It can’t be.’ And it really turns out to be the color of my skin. And then if I get it and it didn’t work, or it did work, would it be because of the color of my skin? That’s a difficult position to put myself into when I don’t need to.”

Not that it really matters. Elba isn’t exactly lacking for world-conquering franchises on his résumé. Not even George Clooney, an actor famous for transitioning from a mega-successful TV career to an incomparable run as a matinee idol and box office star, has had quite as varied a Hollywood studio arc as Elba, though that has as much to do with movie stardom in the 21st century as anything else.

This is the franchise era. In 1997, Clooney did a Batman movie, survived it (barely), and moved on. Elba, by contrast, has had a funny habit of popping up in seemingly every variety of these tentpoles with a fluidness that is probably matched only by Zoe Saldana (Avatar, Marvel, and Star Trek). He’s wound his way through the Alien franchise (Prometheus), the Marvel universe (the Thor trilogy and beyond), Star Trek, Finding Dory, a live-action remake of a classic animated Disney film (The Jungle Book), and Guillermo del Toro’s Pacific Rim (though he was not in its sequel). In an intriguing example of the kind of race-blind casting the 007 movies haven’t yet learned to imitate with their most iconic role, he starred in the 2017 adaptation of Stephen King’s The Dark Tower as the mysterious Gunslinger, locked in eternal battle with Matthew McConaughey. The movie, which is better than you’ve probably heard, tanked. But Elba, gruff and jaded in a riff on bygone Western sharpshooters mixed with more than a little samurai grace, made a case for himself as a genuine star, the kind of person you want to watch in any genre, doing anything.

Race-blind casting is a necessary good for the obvious reasons: Movies aren’t real; most roles can be played by a wide range of shapes, sizes, and skin colors; and our attachment to white actors as cultural defaults has resulted in a lot of samey, boring art—to say nothing of the countless stagnant careers of talented nonwhite actors everywhere. Elba seems particularly proud of his work in the Thor films for that reason. He plays the all-seeing, all-hearing Heimdall, protector of Asgard, a role that the comics, he notes, have typically depicted “as a Norse God—you know, blond, blue-eyed, flowing hair.”

“Suddenly you realize that black kids read comics,” he says. “That whole skater, fanboy crowd—well, black people love these things too.” He got the role by audition: “Kenneth Branagh, who directed the first one, just said, ‘I love you as an actor. I’m going to give you this role.’ ”

Elba says he’s not I.P.-obsessed. “I don’t sit and go, I’m going to take this role because it’s franchisable,” he says. On the other hand, he’s also an actor, and to the extent that ego is involved in these choices, he’s self-aware. “I think it’s one of those pinnacle things that actors strive towards, to have that one character where people go, ‘Ah.’ And it branches off into its own universe and fan base. Every actor loves the idea of having their own franchise.” For him, it has been Luther, the BBC detective show about the brash, impulsive, frequently out-of-line detective John Luther, in which Elba gets to flex a familiar muscle but as the lead, grounding the show’s constant moral vicissitudes in a man we disapprove of even as we root him on. The show is now in its fifth season—and will perhaps, someday, be a movie. “I’d love to see three or four Luthers come out as films, definitely,” says Elba.

It doesn’t escape him, by the way, that when there was once talk of an American Luther, every kind of person was considered: every race, gender, and so on. “It was just whether they could pull off the role,” Elba says, a matter of who was good enough to fill his shoes as the troubled, wearisome, satisfyingly deviant John Luther. The project never moved forward.

What is it that we want to see from Idris Elba? If the legacy of his work as Stringer Bell resulted in parallel but distinct mainstream and black-focused strands in his career, it also solidified a reliable character archetype that, if for no other reason than because he’s so good at it, Elba keeps exploring. In other words, the bad guy. Admit it: You like to see Idris Elba break bad.

Or bad-ish, anyway. You can see how we got here: Bell was a “bad guy,” a drug hustler, but you almost couldn’t help but like him as you hated him. Co-star Michael K. Williams, whose Omar Little has cast an equally large shadow over his career, likened Elba to a sparring partner. Whenever he saw Elba’s name on a call sheet, “I went over my notes extra-hard, and I dotted all my i’s and made sure all my t’s were crossed”—a distinction he afforded only a handful of other actors in the show’s stacked cast. He cried in the makeup trailer before filming Elba’s last scene.

Bell was largely based on Lamont “Chin” Farmer, whom co-creator Ed Burns had once, in his time with Baltimore P.D., investigated and helped prosecute. Simon told me that the real Stringer Bell was a man Burns had admired. “The thoughtfulness with which he proceeded in masking his criminal activity,” says Simon. “He was a very shrewd, very thoughtful, very quiet player.” Hence Elba’s characterization. Handsome, reserved, curiously professional: a guy who approached the project corners with MBA-level discipline—which made him all the more insidious, in criminal terms. Elba’s charm had a funny way of exploiting that tension. Simon describes it as existing between “a layer of street arrogance and confidence” on one hand and “something underneath it that’s contradictory” on the other, some broader intellectual and psychological force at work. This was a strong counterpoint to the more dangerous live-wire Avon Barksdale—the role Elba originally auditioned for. (Ultimately it went to the great Wood Harris.)

Admit it: You like to see Idris Elba break bad. Or bad-ish, anyway.

Elba tells me that it all boils down to his upbringing. His depiction of Bell was somewhat based on a guy he knew growing up, a local weed man who went by “The Gent,” whose attitude was amicable, professional, discreet. “The weed man,” says Elba, “in terms of being portrayed, was always like”—he lowers his voice to a grumble—“big and larger-than-life cat daddy.” But Elba is English: understated, stiff upper lip. He preferred to play it differently, beyond the terms of good and bad. He was there to provide a service. “I’m out here selling bricks,” he says. “Not bricks. I’m out here selling fine furniture, not fine furniture. You know?” Even in his newest film, the upcoming Fast & Furious Presents: Hobbs & Shaw—a spin-off of the internationally beloved Dwayne Johnson and Vin Diesel franchise—Elba plays a bad guy who was, you guessed it, once a good guy. Brixton is his name, though everyone in the movie’s trailers calls him Black Superman because he’s genetically enhanced and apparently unstoppable. For director David Leitch, Elba was a no-contest choice. “I think when you’re looking for someone who can be a formidable adversary for Dwayne Johnson, that’s difficult enough,” says Leitch. “But then you’re looking for someone who can be a formidable adversary for Dwayne Johnson plus Jason Statham. That list gets really short.” The actor is, again, not a franchise nut. Still, he tells me: “I secretly feel like I could make him into a huge character.” He likes playing bad guys. He likes the complexity of those roles, and he’s liking his recent spate of action-movie roles too, which demand a different form of imagination than the usual—and looking beyond the usual, trying new things, keeps him hungry. He doesn’t want to be typecast.

Hence Cats? Alongside Sir Ian McKellen and Dame Judi Dench and Taylor Swift? In which, to be clear, he still plays a “bad guy,” er, cat: Macavity, of whom T.S. Eliot, author of Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats, on which the Andrew Lloyd Webber musical is based, wrote: “He’s broken every human law, he breaks the law of gravity. His powers of levitation would make a fakir stare.” The mind reels wondering what Elba will do with the role. Breaking the law of gravity. I have just seen Elba play a frying egg up close, and I am still not prepared.

Cats director Tom Hooper has long been a fan of Elba’s, particularly in light of his work as Stringer Bell, and had him in mind from his very first draft. What excited him, in this case, were Elba’s other dimensions. “In his other work I’d also seen glimpses of another side to him, a more mischievous, comedic side,” Hooper says. When he and Elba were thinking up a model for the character, Jack Nicholson—who “has that ability to be scary and comedic and unpredictable in the same moment,” says Hooper—came to mind.

Elba has given it a lot of thought. “The myth is that cats have nine lives, and he”—Macavity—“has one left. So he’s desperate to be acknowledged, and he’s slightly unhinged, and he’s obviously met death a few times and gotten past it. The character has complexities, and I think that Tom Hooper…wanted someone who could pull off that stuff—meanwhile singing and dancing and meowing.”

I suspect he can meow. Can he sing? “I’m not a ‘singer,’ ” he says, reminding me that he’s a professional musician. “I’ve made music with singing. I’m musical”—so, no, he’s not a singer per se. And he didn’t see himself starring in Cats until it came time to star in Cats. Hence the appeal. “I’m an actor,” he says. “I’ve never done it before, so I thought, Why not.” He played it cool with me, but according to Hooper, Elba’s excitement was palpable. “It turned out he had always had a dream of being in a musical, which I didn’t know,” says the director. “So Idris got his dream. And he got his dream with Taylor Swift.”

Well, why not? We’re watching Elba’s career explode in real time, and Cats is an enticingly odd cog in that narrative. Rather, we think we’re watching it in real time. Not just his acting career: that Coachella set, the kind of opportunity a DJ works toward for years, was a high point in Elba’s long haul as a professional musician. A few years before that, he had a gig at Glastonbury. He hit a key leading-man benchmark this year when he was invited to host SNL; and just last year, he’d made it to the cover of People’s Sexiest Man Alive, the first black man to do so since Washington in 1996.

It’s as if, all at once, we’ve realized he’s big-league: a mainstream, top-of-the-line success, the kind of actor who can headline 2017’s The Mountain Between Us—an icebound, stranded two-hander costarring Kate Winslet—and maybe pop off a fantasy franchise with Matthew McConaughey and then rumble with The Rock. Elba is aware of how that looks: He’s aware of the pitfalls of what seems, from the outside, like a sudden catapult from medium to mainstream success.

The experience of it was, of course, different. “You know that whole Malcolm Gladwell 10,000 hours,” he says. “I had put my work in. And so yeah, it was sort of like, crawl crawl crawl crawl c-r-a-w-l—stop—crawl—RUN! It really was that for me.” He’d been a working actor for almost nine years before “breaking out” on The Wire; and though many people have only recently become aware of how serious he is about music—a tidbit often used to spice up magazine profiles—this is no mere hobby. It’s easy to write off actors’ secondary careers, be they music or a fashion line, as privileged diversion or mere brand enhancement. And, well, plenty of people putz around on drum sets and turntables in their free time. But this new arc in his music career has been four or five years in the making, Elba reminds me. And this current slate of new releases in theaters and on TV was largely filmed scattershot before 2019. But the calendar happened to work out this year in a way that makes it easy to forget the three or four years when, after coming to the U.S., he was unemployed and losing out on parts to Omar Epps, Don Cheadle, Boris Kodjoe, and Taye Diggs, or the years when he simply didn’t seem to be everywhere at once.

It’s interesting to talk to an actor at this stage of his career about his insecurities, in part because confronting and embracing insecurity is part of the work. Take SNL: a live show pitched, written, and rehearsed within a week, in a genre that—despite his humorous behind-the-scenes persona, which is visible on Instagram, and his brief but hilarious stint on The Office—isn’t necessarily seen as his bag, even if it should be. Elba enjoyed being on the program: “It was fun. It was really hard work—honest, hard work.” He likes that. But he also had to open himself up. “I found that, you know, the more I just plugged in, and jumped headfirst in, and just exposed myself and my insecurities to anything, the better it was for me as an experience,” he says.

He shows his insecurities to us all the time. We likely don’t experience it in quite those terms. But Elba does. “You’re throwing yourself out there for people to pick at you, or steer you, or tell you their opinion, or laugh at you, or celebrate you,” he says. “Whatever those are, you’re definitely amplifying that.” Growing comfortable in that space isn’t easy for him, or anyone. Just look at other actors. “Daniel Day-Lewis is an incredible actor,” Elba says, “but does not like to be in the public eye and manages to do the two. I can’t do that. I wish I could. I wish I could just be obscure, and no one ever have to see me, and never have to do interviews, and still have the career that he has.”

This is part of what makes celebrity in the 21st century uniquely difficult. Day-Lewis was already an Oscar winner by the time Elba arrived on the scene; he’d likely have faced a different climate coming up today, in an age of social media, where an engaged and personable performer like Elba is expected to wield his online clout in one way or another. “As you climb up the ladder,” he says, “people expect you to have way more followers, and you become the marketing engine. There used to be a day where I could have no followers and still get paid and people still expect me to do press. But if I come along with 8 million followers, and they’re all going to see my movie, the film companies want that. So the pressure to be more public is higher.” Gone, in other words, are the days of “saying whatever the fuck I wanted” on Twitter. “And if you take a picture of you, or your house, do know that there are people zooming in to see what’s behind you,” he says. “That stuff—you have to think about it way more than people back in the day.”

He doesn’t love it. But he’s mastered it. When we talk again in a few weeks, Coachella has come and gone, and so has the actor’s three-day Morocco wedding—a private event made public by virtue of who Elba is, with splashy photos published in British Vogue and the collectively disappointed sigh of woeful admirers around the world. He met Sabrina Dhowre at a party in Toronto while filming The Mountain Between Us, which can’t help but feel somehow quaint, even normal. That seems to be the ideal. “Everything’s a balance in life,” Elba says. “I have to do the work, because it’s a popular time for me, and it’s best to have that. But also: I’m madly in love with my wife and my children.” They’re his priority, still: not fame, not persona, but the Canning Town boy become man, and the people he loves. “At home, I’m not famous: I’m me,” he says. “And to my team and my family and the people that I work with every day when we build what we build, we’re not famous. You know what I mean? It’s day one every day.”